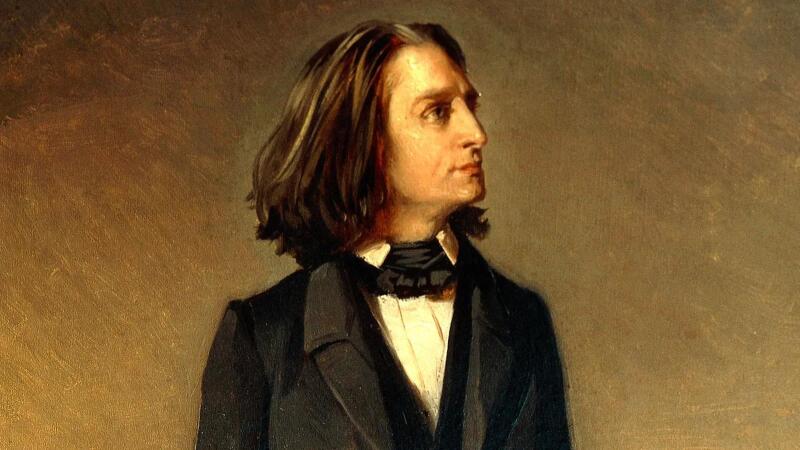

He couldn’t get it out of his head for a week, said Professor David Trippett of Cambridge University of a melody he found in a manuscript by Liszt, held in Weimar and all but ignored for 170 years. First mentioned in print in 1911 and the subject of numerous studies since, the manuscript had been considered fragmentary and impossible to perform – until Trippett and his team deciphered it and found it to be the only surviving act of Liszt’s opera, Sardanapalo. A world première 130 years after the composer’s death; the discovery and reconstruction of a priceless 111-page manuscript: all the details are here.

Who was Sardanapalus?

He lived for peaceful earthly pleasures instead of war, for humanity instead of violence, for wine and women instead of weapons. This is the image of Sardanapalus (Ashurbanipal), king of Assyria, as handed down to the 19th century by a Greek author. Delacroix and Liszt were fascinated by the same scene in Byron’s tragedy about the monarch, that of the king’s death. In 1828, Delacroix painted the scene, while Liszt intended to write a finale for a three-act opera that would exhilarate audiences.

How Does a Genius Who Composed an Opera at the Age of 13 Choose a Subject?

In the 19th century, many aspired to write a successful opera – French at least, but preferably Italian – as a composer’s calling card that would open doors to quick and widespread success. This was exactly what Liszt was considering in the early 1840s, at the height of his career as a piano virtuoso, when he repeatedly declared his intention to leave the concert platform and pursue a career as a composer. He had already written an opera at the age of thirteen, but the success of Don Sanche proved short-lived, having been performed only four times – albeit in the ultimate French citadel of the genre, the Paris Opéra (much to the envy of many). The time had come for the adult Liszt to look for a suitable subject. Among other things, he considered Walter Scott’s Richard en Palestine, Byron’s Corsair (later adapted as an opera by Verdi), a proposed treatment of Jeanne d’Arc by Friedrich Halm, Dante’s Inferno, Goethe’s Faust, and even a work with a Hungarian subject, Karl Beck’s Jankó. Finally, in 1845, he chose Byron’s drama, Sardanapalus.

Complications around the Libretto

Finding a subject is the least of the troubles that an ambitious composer faces. The next, more arduous step is acquiring a libretto. Liszt first commissioned Félicien Mallefille to prepare an adaptation of the tragedy, but he failed to deliver in a timely manner. When, in December 1846, Liszt finally received the French prose text – which was yet to be translated into Italian verse, and then set to music, and with the première planned to take place in May 1847 in Vienna – he paid two thirds of the fee and sent Mallefille packing.

Hovering over the enterprise like a guardian angel was Cristina Belgiojoso, a close friend of Liszt’s, who was originally set to edit Mallefille’s text and perhaps also help with the translation. When Mallefille’s tardiness started to be a cause for concern, Belgiojoso took matters into her own hands and had an Italian poet write the libretto of the first act. The princess imposed only one condition on the collaboration: she would not disclose the identity of the author, a secret she kept so well that we still do not know who the poet was. Liszt was very pleased with the libretto, of which, however, no original copy has survived; the only version we know is what he copied into the music – with lots of mistakes.

David Trippett Solves a 111-page Puzzle

As became clear to David Trippett, the 111-page draft Liszt left behind is continuous. Earlier scholars were in agreement that it was a set of barely legible, fragmentary sketches – but those looks are deceptive. The gaps in the notation for the voice parts and piano appear because Liszt only wrote down what did not follow unequivocally from its precedents. Often, only the first bars are provided of the rhythmic scheme of the accompaniment, after which the notation is restricted to the harmonies. Trippett therefore “put on Liszt’s shoes” and reconstructed the music by way of analogies, without composing original material. As regards the orchestration, he followed the composer’s notes (as would Joachim Raff, one of Liszt’s Weimar students, who completed arrangements for him), and wherever these were missing, he resorted to solutions used in the works Liszt composed and performed at the time. To solve practical issues of performance style, Trippett reached out to singers (Anush Hovhannisyan, Samuel Sakker and Arshak Kuzikyan), while the libretto was restored by Marco Beghelli, Francesca Vella and David Rosen.

It was inconceivable for a 19th-century musician and composer not to be at home in the world of Italian and French opera. Nor could visitors to Paris salons remain untouched by its influence. Chopin transposed the melodiousness and vocal ornamentation of bel canto to the piano, while Liszt arranged popular motifs in a series of virtuoso paraphrases. The music of Sardanapalo is rich in interesting choices, fascinating even as a one-act torso, because while reminiscent of the styles of Bellini, Verdi and Meyerbeer, the melodies – which start in stereotypical ways – continue to take unexpected turns, and all this is combined with a German harmonic vocabulary, a touch of Wagner and, most importantly, a real Lisztian zest.

The Unfinished Masterpiece

One can only speculate why Liszt did not continue work on the opera after 1851. Trippett believes the main reason is that no libretto was forthcoming for the second and third acts. Wagner may also have played a part in the abandonment of the work, as he became increasingly vocal about his aversion to Italian opera and his intent to reform the genre. (In 1850, Liszt himself conducted Tannhäuser and Lohengrin in Weimar.) Liszt, however, evidently had serious intentions with his own opera because he did not destroy the manuscript or salvage any of the musical material for other works. Nor did he give up on the ideal of dramatic music based on a coherent narrative, as is evident in the twelve symphonic poems he wrote and his continual commitment to the concept of programme music.

A World Première 170 Years Later

Thanks to years of painstaking work by Trippett and his team, the first and only completed act of the opera had its world première in Weimar on 19 August 2018. The Audite label released a recording of the piece in February 2019 (performed by the Staatskapelle Weimar under the baton of Kirill Karabits, with singers Joyce El-Khoury, Airam Hernández and Oleksandr Pushniak), while in November that year, Editio Musica Budapest published a critical edition of the voice and piano version. Liszt Fest now presents the piece in Hungary: the very same performers at the world première can be heard in the Béla Bartók National Concert Hall on 22 October 2023. Though Professor Trippett would not rule out a staged performance of the one-act opera, that is something we are yet to see…