Weimar, the city of Goethe and Schiller, held special significance in Franz Liszt’s life, a place where he always found peace. We examine its role in light of an October concert at Liszt Fest.

“The time has come for me (nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita – thirty-five years old!) to break out of my virtuoso’s chrysalis and allow my thoughts unfettered flight,” Liszt wrote “halfway through the journey of life,” a notion that can be taken as the artistic credo of the composer in his prime. He had achieved all that was possible at the time, and more: he was the first modern pianist to provoke hysteria by his mere appearance, and – through the genre of the solo piano concert – was the prototype of the modern pop star pushing droves of musicians into jealous despair. When near a piano factory, he was routinely invited to touch the instruments with his fingers, permitting them to be sold for many times the price.

But Liszt’s name would be mentioned far less frequently if he hadn’t listened to reason in the 1840s – and to some of the cool-headed advisers around him. Because there were plenty of virtuosos in the cities of the 19th century, and even if Liszt was the best of them, many still considered him just another disciple of what Heine called the “flying-trapeze school”: furiously fast and overwhelming. Even if Liszt’s virtuosity was deeply musical, he could truly impress only the most sophisticated listeners, and the compositions he wrote for himself clearly rivalled only those that other contemporary virtuosos committed to paper.

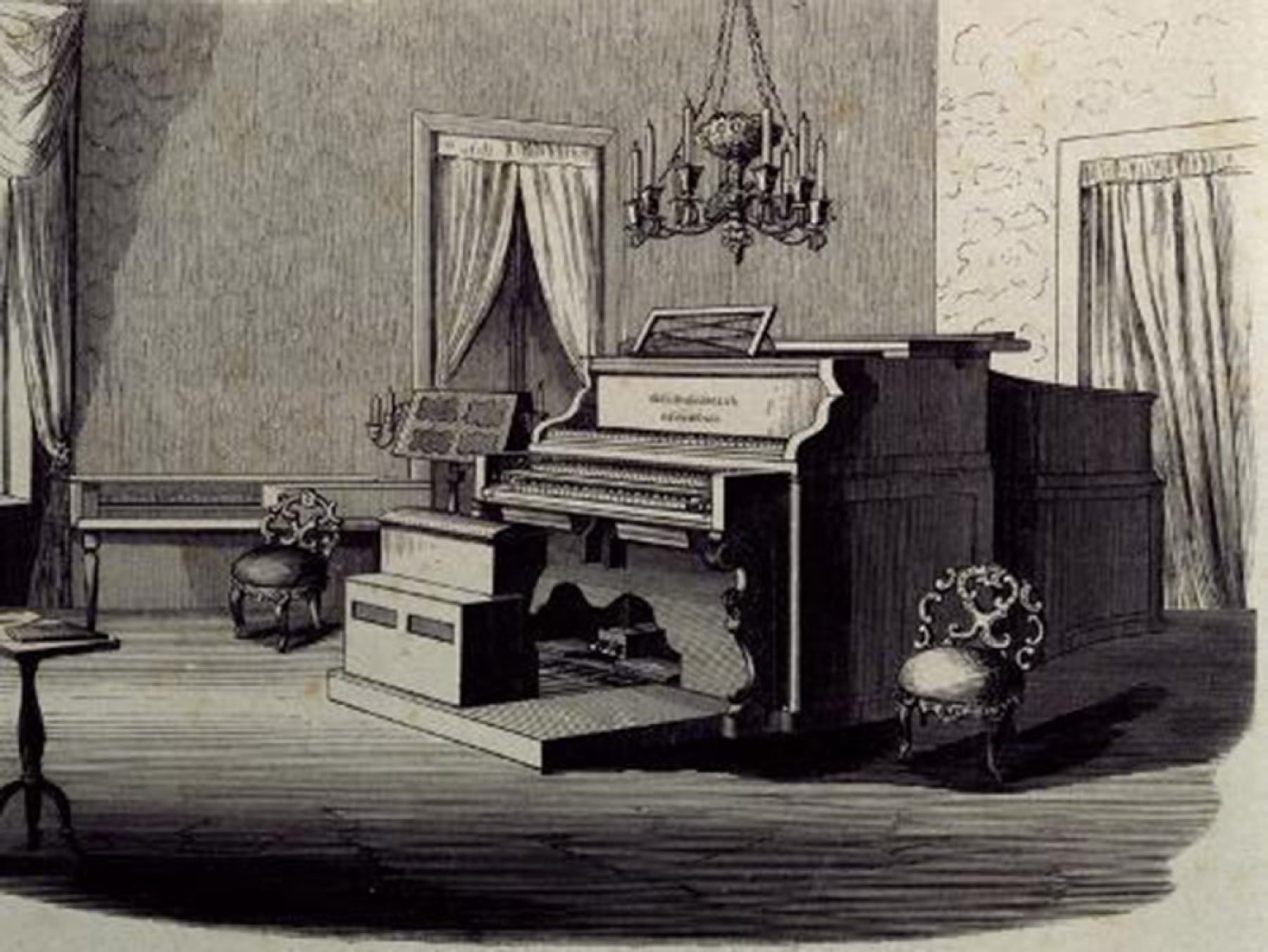

The music room of Liszt's home in Weimar, the Villa Altenburg

The music room of Liszt's home in Weimar, the Villa Altenburg

It may sound clichéd, but Liszt did live like a rock star in the 1840s: he generally squandered the money he earned and took out loans to cover his expenses, which he then paid off with the next big concert. The endless series of banquets and receptions wore him out, as there was not a city or mayor that did not want to give him at least a medal or an award as a token of their appreciation.

So Liszt changed his ways. In February 1848, he moved to a small German town to take up the post of director (Kapellmeister) of the local orchestra, the Staatskapelle Weimar. This move was not unlike the Beatles when they stopped touring, turning their back on packed stadiums and hysterically screaming teenagers so that they could return to the studio and make epochal albums.

Weimar had a significance that far exceeded its small size: once the home of Goethe, Herder and Schiller, it was a centre of European humanism, with a theatre, an orchestra and a large population of poets, painters and scientists. Situated a mere twenty kilometres from Jena, home to one of Europe’s best universities, and with undisturbed peace reigning, Weimar presented an unmissable opportunity for Liszt to pull himself together and reinvent himself.

One of Liszt’s sober advisers was the Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, the wife of a German nobleman, whom Liszt met in 1847. The two fell in love but were prevented from legitimizing their union because Carolyne could not get a divorce, even though she pleaded with the pope himself. More importantly for our topic, Carolyne was an exceptional woman who persuaded Liszt to devote the next few years to composing.

Liszt himself probably knew that this was what he had to do. He was one of those musicians who understood the times in which they lived. He knew that while composition and performance went hand in hand in previous centuries, this had changed with Beethoven. While Bach and Mozart did not necessarily expect their works to live forever, it seemed that composers after Beethoven – Romantic geniuses who stood above their own time – were supposed to create masterpieces like the Ninth Symphony. Liszt was the first to propose that a “music museum” be set up in the Louvre, where important works would be preserved and performed for centuries.

In this light, it is hardly surprising that in the late 1840s Liszt saw that the time had come for him to produce great works of his own.

Weimar seemed the ideal location for such ambitions: Jena, Erfurt, Sondershausen and Bach’s birthplace, Eisenach, were all part of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Liszt hoped that the city could be a breeding ground for new music, just as it had fostered philosophy and poetry a few decades earlier, while also connecting modern art with the past. It was no accident that in the 1850s this “famous (and tireless) musician of the world” presented concerts of both the “music of the future” – the works of Wagner and Berlioz – and the oratorios of Bach and Handel.

Liszt knew where music history was coming from and where it was going.

The 1850s were an exceptionally fertile period for Liszt, the composer. While the previous two decades saw him “squander” his talent (strictly in inverted commas!) on opera paraphrases, fantasias and rhapsodies, once he took the job in Weimar he produced one important work after another. In truth, his first undertaking may not have been cut out for him: he wrote down the first notes of Sardanapalo in 1845, only to abandon the opera seven years later. The one surviving act of the piece, which was based on Byron’s poem, was presented only 130 years after his death, in Weimar in 2018.

The motivation Liszt gained from his access to an excellent orchestra is hard to overstate, as is the brilliance of the symphonist he evolved into. This period was marked by the symphonic poems Tasso, Les Préludes, Mazeppa and Orpheus, and two of his major symphonies.

The Staatskapelle Weimar is one of the oldest ensembles in Europe: its predecessor was founded in 1491, during the reign of Frederick the Wise. Liszt’s arrival in 1848 ushered in one of its most successful periods (while the next was overseen by Richard Strauss at the end of the century). Weimar became the Mecca of modern music, and many of Liszt’s works were first performed by the orchestra. In 1857, it was the Staatskapelle that premiered the Faust Symphony, Liszt’s stunning 75-minute stream of consciousness that offers a portrait of the three main characters of Goethe’s drama. The ensemble was also the first to perform the Dante Symphony, whose gestation period was particularly long: the composer first played excerpts on the piano for Carolyne in 1847 or 1848, but he did not draw the double bar at the end of the score until 1856.

The composer was permanent conductor of the orchestra until 1858. He suffered personal tragedies over the next decade, and it was in the church that he later found new creative perspectives. Weimar, however, was to remain his “sanctuary” until the end of his life.

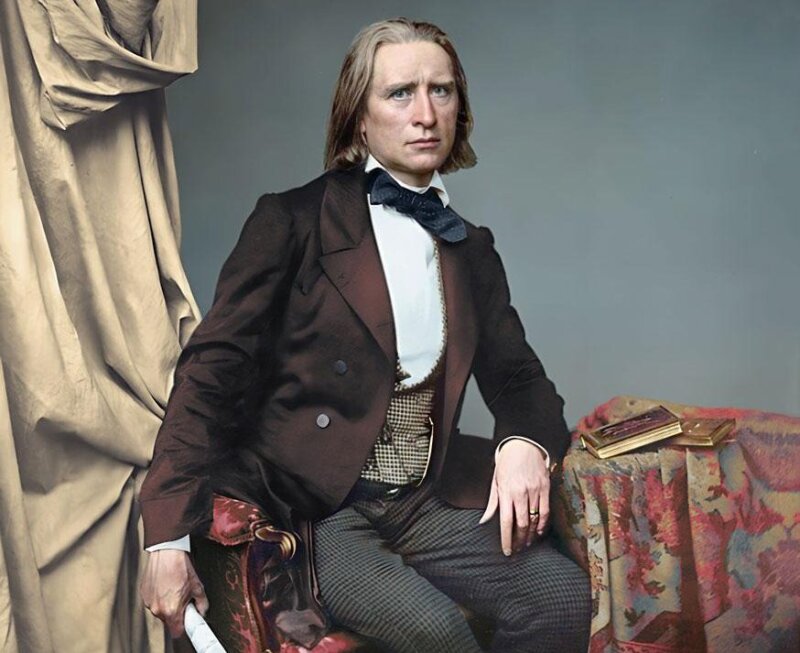

Liszt's former homes, the Villa Altenburg now serves as a music school

Liszt's former homes, the Villa Altenburg now serves as a music school

Traces of the composer can be found all around the city. As Kapellmeister, Liszt lived in the Villa Altenburg, a three-storey building that now houses part of the music university bearing his name. A museum dedicated to Liszt is housed in his second home in Weimar, on Marienstrasse, near the beautiful, verdant Ilm Park. The composer stayed at the understated, two-storey villa with yellow walls in the summers of 1869 and 1886, which is to say not during the period music historians call “the Weimar years.” There is a beautiful Bechstein piano in the salon, along with Beethoven’s death mask.

Liszt eventually left Weimar due to intrigue in the city and problems in his personal life: one could say his modernity was not understood, but he himself never embraced the role of the victim. He went on to redefine himself once again, and towards the end of his life even graced Budapest with his presence.