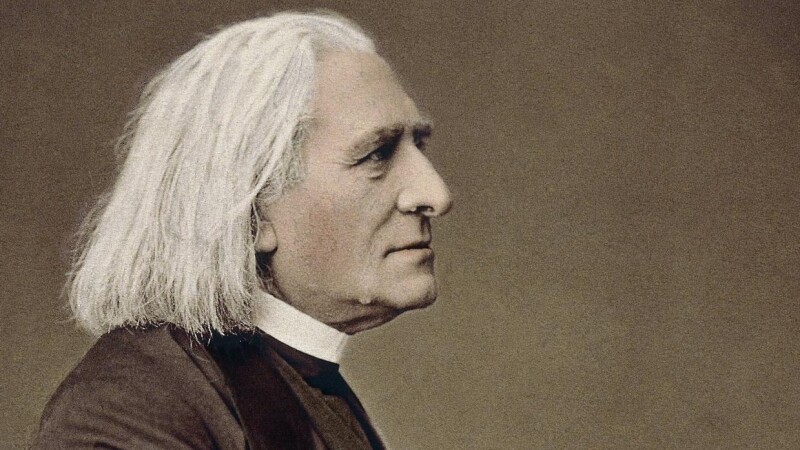

“All things are transient, only the word of God remains eternal – and the word of God is manifested in the works of genius,” said Franz Liszt, who wanted to become a priest from a very young age. His father, Adam Liszt, envisioned a different career for him, even though he himself had considered a religious vocation and had been a novice in the Franciscan monastery in Malacky (Malatzka), only to leave the order before taking his vows. “You belong to music and not the church,“ he urged his son. At the time Franz bowed to his father’s demand and relinquished the calm of life in the clergy for the restless ways of the artist.

After his father died in 1827, Liszt, who was still only 17, gave up on concert tours and the concomitant lifestyle and returned to Paris, where he made a living by giving piano lessons. He lived with his mother in a small rented flat and, harried by his schedule, quickly took to smoking and drinking. He was emotionally and physically broken by his inability to secure the approval of Caroline de Saint-Cricq’s father to their marriage, and the slight plunged him into such deep melancholy that the papers in Paris reported him dead and L’Etoile published an obituary. While his depression lasted, he repeatedly revisited the idea of taking holy orders: “I have felt it to the depths of my heart from the age of 17, when with tears and supplications I begged to be permitted to enter the seminary in Paris, and I hoped that it would be given to me to live the life of the saints and perhaps the death of the martyrs.” It was during this period that he met Abbé Felicité Lamennais, who became not only his spiritual guide, but also a trusted friend privy to his deepest secrets.

Liszt’s religious interests became overridden by a surging desire to make music again – awoken by the experience of hearing the devilish violin playing of Niccolò Paganini – and a romance with Countess Marie d’Agoult, an extramarital affair from which three children were born. In 1839 he set off on a tour, and for the next eight years visited the great cities of Europe, from France to Germany and Russia. While many consider this to be one of the most successful periods of his career as a concert pianist, Liszt grew more and more desirous of a peaceful, ordinary way of life. He would ease the frantic pace of appearances after he met Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein in 1847 in Kyiv, where she was on a business trip. She convinced him to change his lifestyle and he moved to Weimar, where he became closer to religion again, turning to God in his prayers. He was not swayed in his Catholicism even when Pope Pius IX withdrew – at the last moment, after years of pleas – his permission for marriage with Carolyne. By 1864, when all obstacles to the marriage had been removed, Liszt had already decided to fulfil his youthful dream and take his priestly vows.

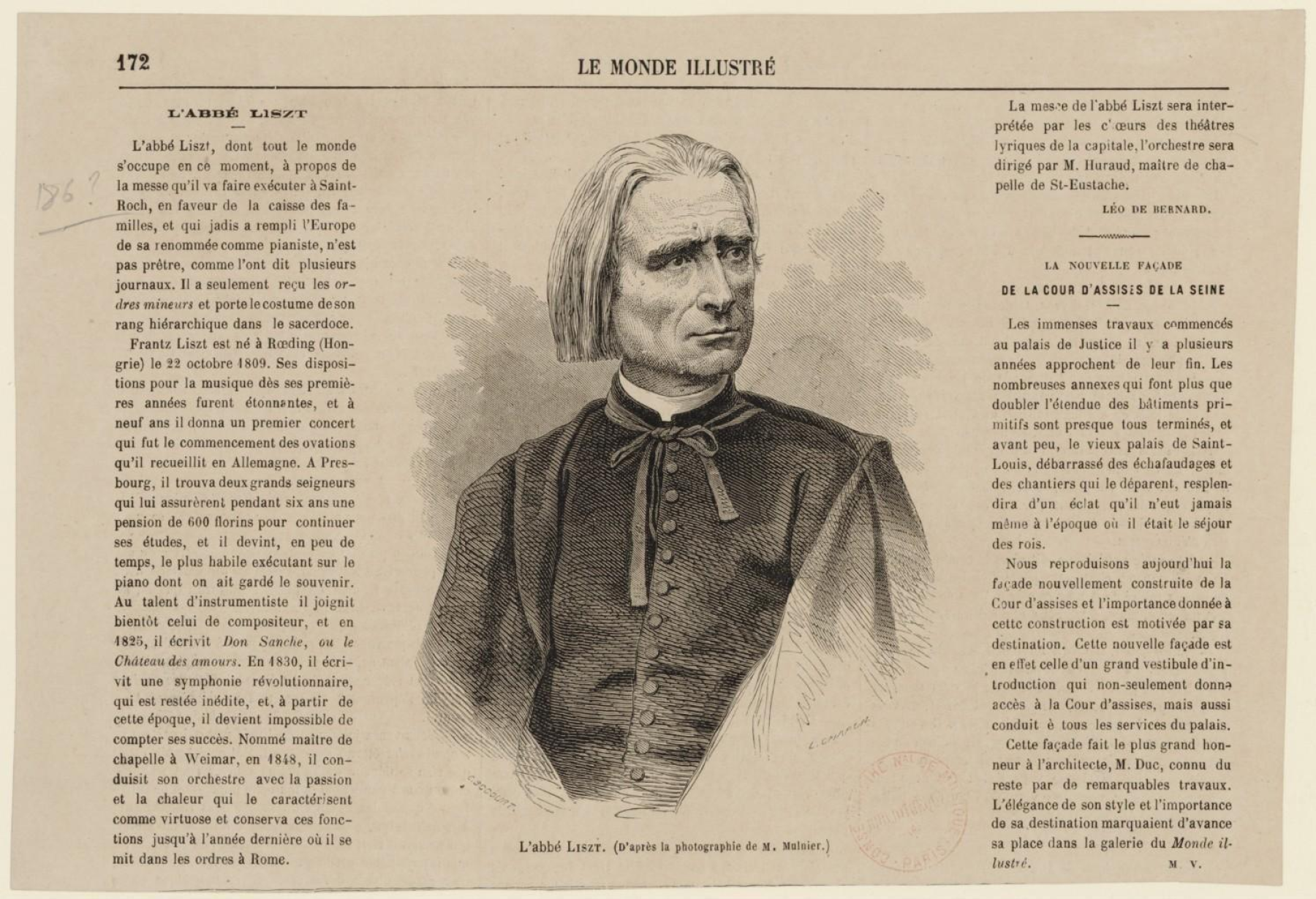

Article in Le Monde Illustré Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Many believe Liszt was motivated by tragedies in the family: in 1859, his son Daniel died of an unknown illness, and then three years later his eldest daughter Blandine perished in childbirth. In 1863, Liszt moved to the Madonna del Rosario Monastery near Rome, and in 1865, in the private chapel of Cardinal Gustav Hohenlohe, he took the four minor holy orders, becoming what today would be called a deacon, a rank below that of an ordained priest. “I am particularly attached to Rome, where one day I hope to rest for good and repeat after Bernard of Clairvaux: ‘Here the air is clearer, the sky is more open, God is closer’.” From then on, Liszt was mostly seen in his distinctive dark cassock, which he wore until the end of his life and which it was his wish to be buried in. He came to be referred to as Abbé Liszt, a phenomenon that a friend in Rome, Ferdinand Gregorovius, described thus: “Mephistopheles disguised as an abbé. Such is the end of Lovelace.”