You don’t need to be particularly well versed in music history to have heard of Franz Liszt, the greatest Hungarian composer of the 19th century, who set out as a child prodigy and earned world fame as a pianist. But it would be a mistake to typecast him on the strength of these two attributes because he had countless other faces as well: a conductor, an educator of wide reach, a bold innovator and a musical writer. This miniseries is dedicated to the perhaps less familiar aspects of the festival’s namesake.

Like every virtuoso, Franz Liszt was often accused of using his performing skills to show off his own greatness rather than that of the work. However, as Liszt himself once said, “To play Beethoven well requires a little more technique than is required.” Technical superiority can therefore serve nothing but the work and its author. There is not a single bar even in Liszt’s most technically challenging pieces that does not bear witness to the composer’s thorough knowledge of the anatomy and mechanics of the hand and arm, as well as of the instrument.

Statue of Liszt's right hand, by Alajos Strobl (1884) Franz Liszt Memorial Museum

Like Beethoven, Liszt could span twelve keys with his hand; for comparison’s sake, Daniel Barenboim, one of the best-known pianists of our time, has a hand span of “merely” nine keys. In addition to the size of his hands, their unusual anatomy was also crucial to his success. Liszt’s knuckles were exceptionally narrow and long, especially on his ring finger, and he could exert an unusual amount of force with his little fingers. As in the case of Rachmaninoff, it has been proposed that Liszt may have had Marfan’s syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the connective tissue and whose characteristic symptoms include skeletal abnormalities, including thin, spidery fingers with loose joints.

Legend has it that on one occasion he was holding a burning cigar between his index and middle fingers while he accompanied a barely 15-year-old Joseph Joachim through a performance of an arrangement of Mendelssohn’s violin concerto. However, few instruments could long withstand his dynamic playing style and vehement strokes, and some pianos gave up the ghost under Liszt’s hands during one concert or another.

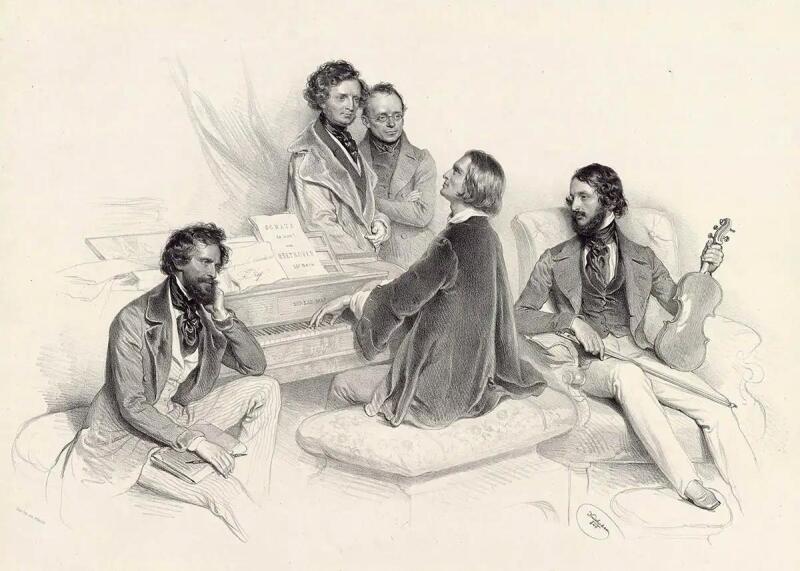

Ein Sonntagskonzert im Hause Liszts, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

The crisscrossing of hands and musical effects, the notes tumbling forth in an almost incomprehensible quantity, were not committed to paper merely for the sake of their dazzling effect: they perfectly illustrate the nature of the musical ideas swirling in Liszt’s mind. The same could be said of his works written for the orchestra. As Alan Walker wrote in his biography of the composer, “Liszt treated the orchestra as he treated the piano, as an instrument of virtuosity, there to be conquered and turned into a tool of musical expressiveness.” The birth of a musical idea is often preceded by long labour, whereas Liszt wrote with incredible speed and particularly liked to work on several pieces at the same time. He once told how, while busy notating the Credo movement of the Esztergom Mass, he ”almost entirely” developed four other movements in his head. Given this pace of work, it is perhaps not surprising that he left behind nearly 1,400 works, including both originals and transcriptions, becoming one of the most prolific composers of all time.